Eduardo Chillida

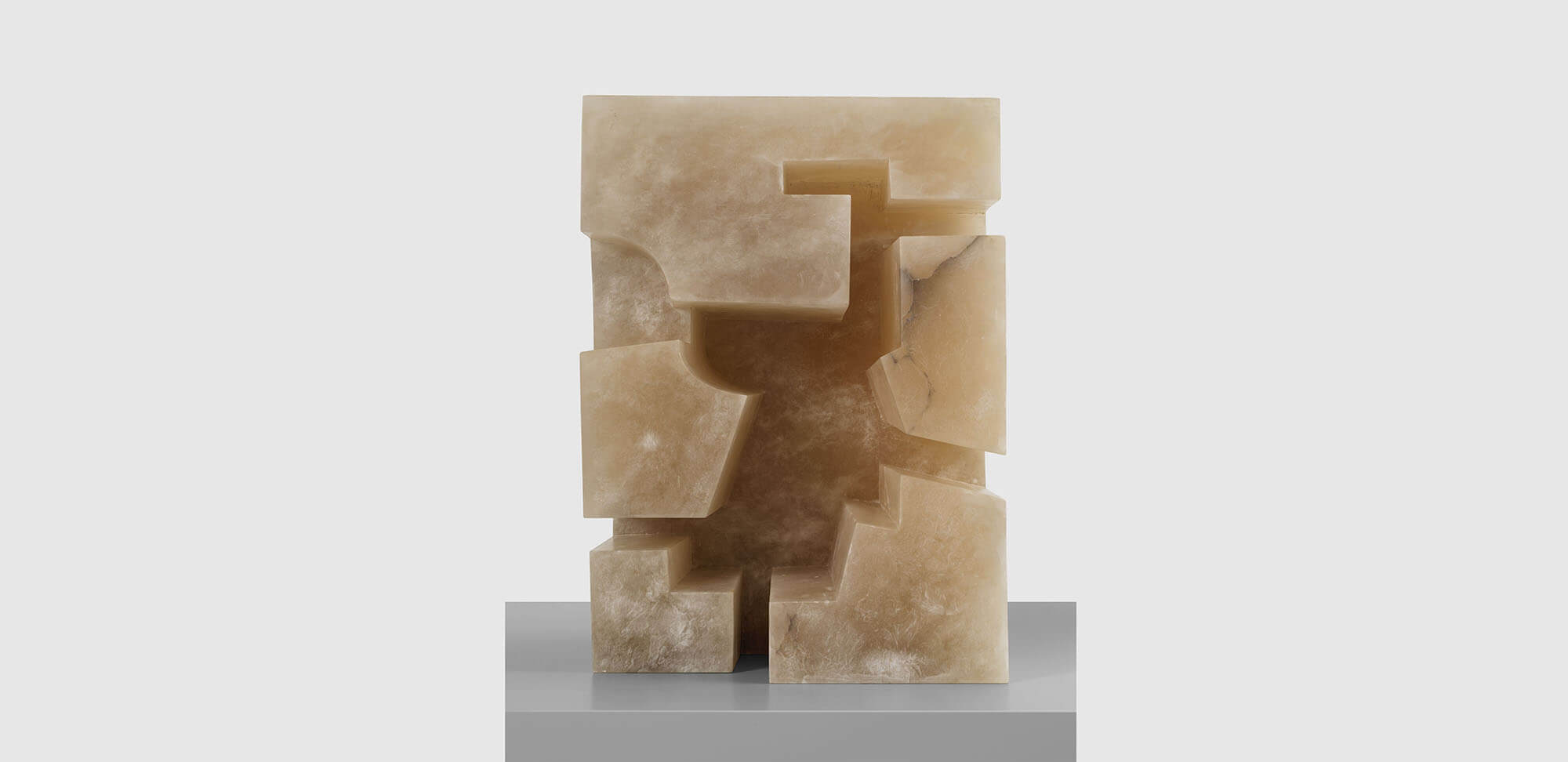

Homenaje a la Arquitectura II (Homage to Architecture II)

Homenaje a la Arquitectura II (Homage to Architecture II)

2000 Alabaster 88.9 x 50 x 62 cm / 35 x 19 ⅝ x 24 ⅜ in

Homenaje a la Arquitectura II (Homage to Architecture II)

Throughout his career, Eduardo Chillida created works in tribute to various figures that he respected and admired. Titular structures of these works include 'Homenaje a' ('Homage to'), 'Casa de' ('House of'), 'Estela de' ('Stele of'), 'Saludo a' ('Salute to') and 'Mesa de' ('Table of'). Chillida's homages fell into three broad groups: he dedicated pieces to artists including Constantin Brancusi, Alexander Calder and Joan Miró; musicians like Juan Sebastián Bach and Antonio Vivaldi (the latter of whom provided the basis for his first work in homage, in 1952); and philosophers and poets such as Martin Heidegger, Gaston Bachelard and Pablo Neruda. In full, Chillida's homages come out to more than 80 sculptures, 58 prints, and two drawings.

Made just two years before Chillida's death, 'Homenaje a la Arquitectura II (Homage to Architecture II)' (2000) is an homage not to a creative figure whose work the artist admired but to architecture itself. Chillida studied architecture at the University of Madrid from 1943 to 1946 and then abandoned his studies to pursue drawing classes at a private art school. In 1948 he would leave to Paris and turn his focus to sculpture, which would occupy him for the rest of his life. Sculpture fundamentally shares with architecture a necessary concern with the realities of gravity. Chillida's architectural understanding shows in his sculpture to an even greater extent, through his attention to spatial relationships and materials (notably, the iron and steel that the artist so often employed in his sculpture referenced Basque traditions in architecture and industry).

Markus Müller observed that as Chillida matured, his sculptures only become more architectural: 'The expressive, space-consuming and dynamic gestures of the early iron sculptures are followed… by rather closed individual cubic forms in nested tectonics. The French concept of 'architecture sculpture' describes this innovation very aptly'. [2] 'Homenaje a la Arquitectura II' has the confident, compact volume characteristic of Chillida's late sculpture. Emerging from various geometric cutouts in monolithic rock, the work is formed through interactions between positive and negative space. Chillida saw his sculptures as expressing the 'essence' of the materials he used, which included iron, steel, wood, plaster, and stone. While Chillida may be more widely known for his work in steel and iron, materials which featured prominently in his oeuvre, he carved 'Homenaje a la Arquitectura II' from alabaster. The artist became enamored with the material during a 1963 trip to Greece, and would make his first work in alabaster in 1967. The translucence of the alabaster allowed light to pass through voids, emphasizing the play between positive and negative space that was so central to Chillida's practice. In this softly luminous material, intricately carved, Chillida created the visual puzzle that is 'Homenaje a la Arquitectura II'.

[1] Eduardo Chillida quoted in Kosme de Barañano (ed.), 'Chillida 1948-1998', Madrid/ES: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 1998, p. 62. [2] Markus Müller (ed.), Eduardo Chillida, Munich/DE: Hirmer Verlag, 2011, p. 34.

Eduardo Chillida

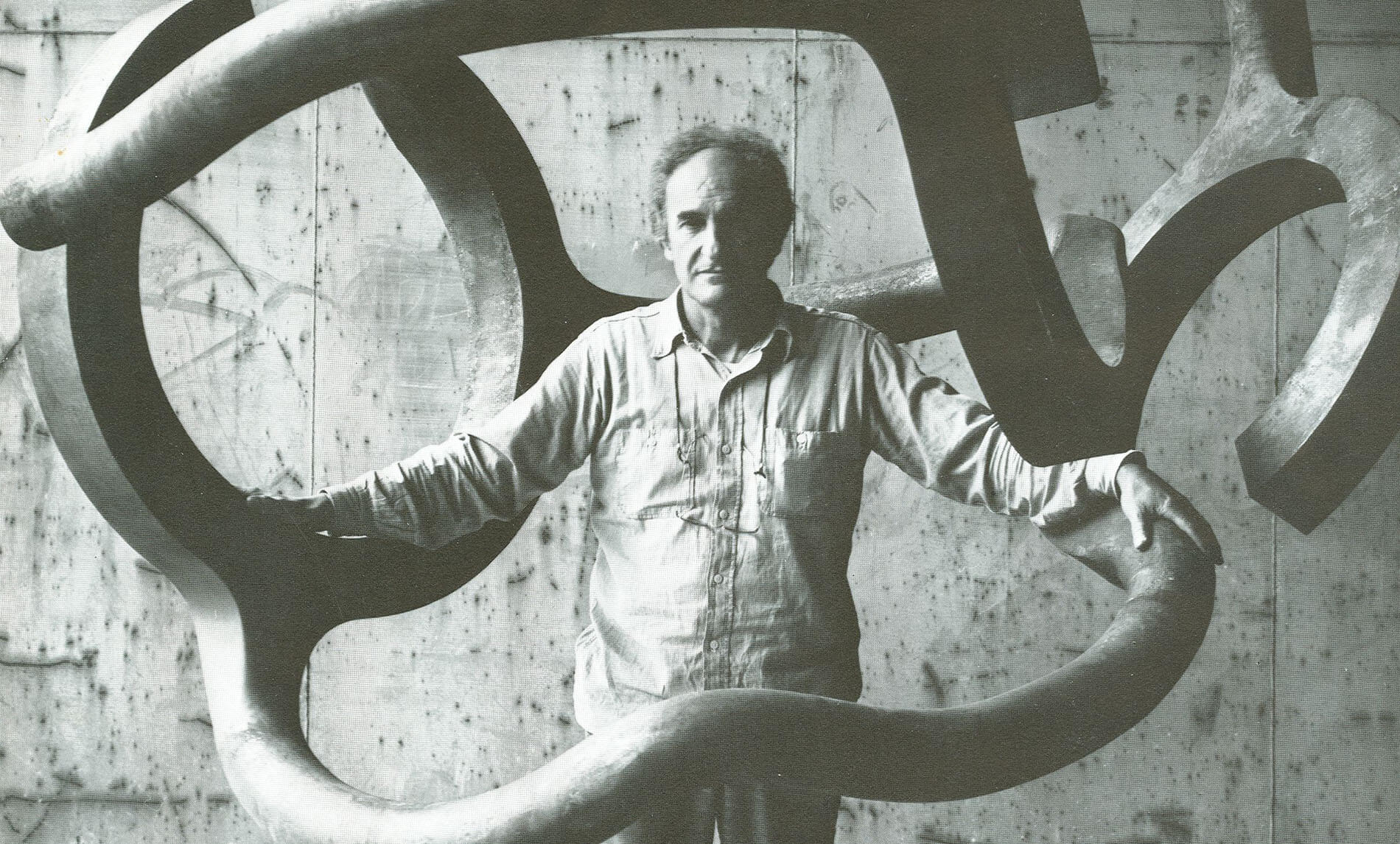

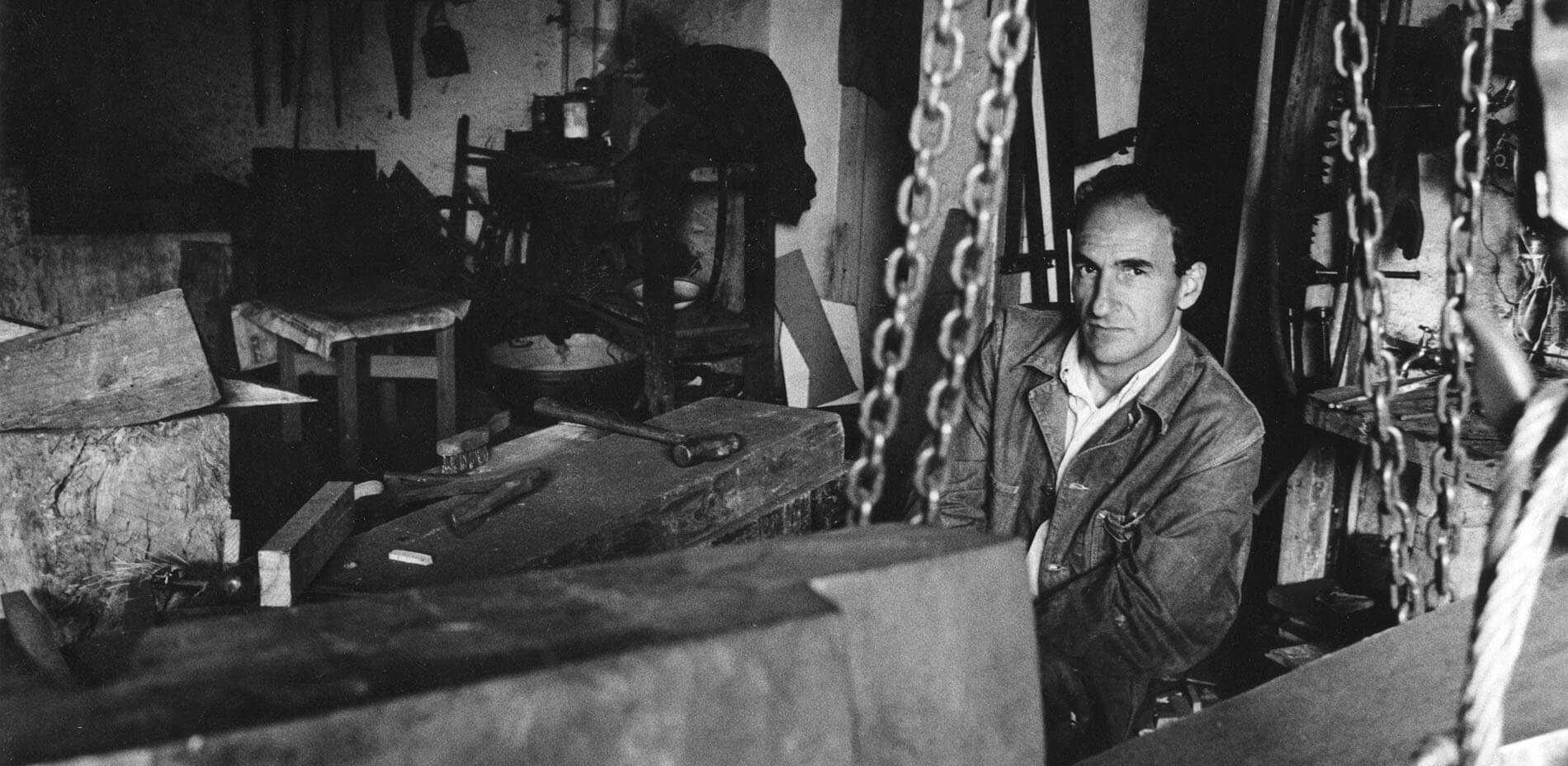

With a varied and pioneering practice that spans small-scale sculpture, plaster work, drawing, engraving and collage, Spanish artist Eduardo Chillida is best known for his prominent monumental public sculptures, mostly displayed in Spain, Germany, France and the USA. Throughout his career, Chillida drew on his Spanish heritage combined with a fascination for organic form, as well as influences from European and Eastern philosophies, poetry and history, to develop an artistic voice that communicated and resonated with a continent undergoing rapid transformation.

Originally a student of architecture, Chillida created art guided by its principles. His formally rigorous constructions in oxidised iron are imbued with tension and poise. Chillida’s contribution towards Spain’s postwar artistic reputation and his personal legacy endure through his work and also through the Foundation which he set up in 2000. In the same year, Chillida opened Chillida Leku, an exhibition space and sculpture park converted from the historic Zabalaga farmhouse in the town of Hernani, near San Sebastian.

Eduardo Chillida in the studio at villa Paz 1965. Photo: Sydney Waintrob, Budd Studio N Y.

‘Form springs spontaneously from the needs of the space that builds its dwelling like an animal in its shell. Just like this animal, I am also an architect of the void.’—Eduardo Chillida

Eduardo Chillida: Sculptor

Jed Morse, Chief Curator, Nasher Sculpture Center, talks about the work of Eduardo Chillida (1924 – 2002). Widely recognized for monumental iron and steel public sculptures displayed across the globe, Chillida is also celebrated for a wholly distinctive use of materials such as stone, chamotte clay, and paper to engage concerns both earthly and metaphysical.